That's right, another feast! Who says the Church is only about fasting - the rhythm of the Church is a balance of fasting and feasting, a discipline of feasting without slipping into self-indulgence, and fasting without slipping into self-abuse. Or maybe to put it another way, the fasting prevents us from too much feasting, and vice versa.

So today, September 14th, is the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. This feast actually commemorates three historical events:

1) When the emperor Constantine's mother, Helena (known to us as St. Helena), identified the actual place of the crucifixion and burial of Jesus. This wasn't difficult because the Christian inhabitants of Jerusalem knew exactly where they were, and in fact an earlier emperor had tried to obscure them by paving over them and building a pagan temple there. The new self-identified Christian emperor, Constantine, had the temple torn down, and excavated the sites, and there they found the tomb of Jesus, which contained the True Cross - the cross-beam of Christ's Cross. (The way crucifixion actually worked was that the vertical beam was permanent in the ground outside the city gate, and only the cross-beam was carried by the condemned, and so to take a person down from a cross - especially one who was nailed to it - you had to take the cross-beam down, too, and then pull out the nails on the ground, or if the tomb is very close - which it was - you carry the person and the cross-beam into the tomb to stay out of sight, and you remove the nails there, presumably setting the cross-beam aside to care for the body, and the cross-beam gets forgotten there. Tradition says Helena also found the nails.).

2) St. Helena commissioned (and her son Constantine paid for) the building of two basilicas right next to each other, which is now the whole complex of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (it includes a basilica dedicated to the crucifixion, a central courtyard over the exact site of the crucifixion, and a basilica over the tomb, which of course is also the site of the resurrection). So September 14th is the date of the dedication of the Church complex. Both of these events took place in the 4th century.

3) The relic of the True Cross was divided into pieces, but the piece that was left in Jerusalem as the main relic at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was stolen by Muslim invaders in the 7th century. September 14th also commemorates the day it was recovered and brought back.

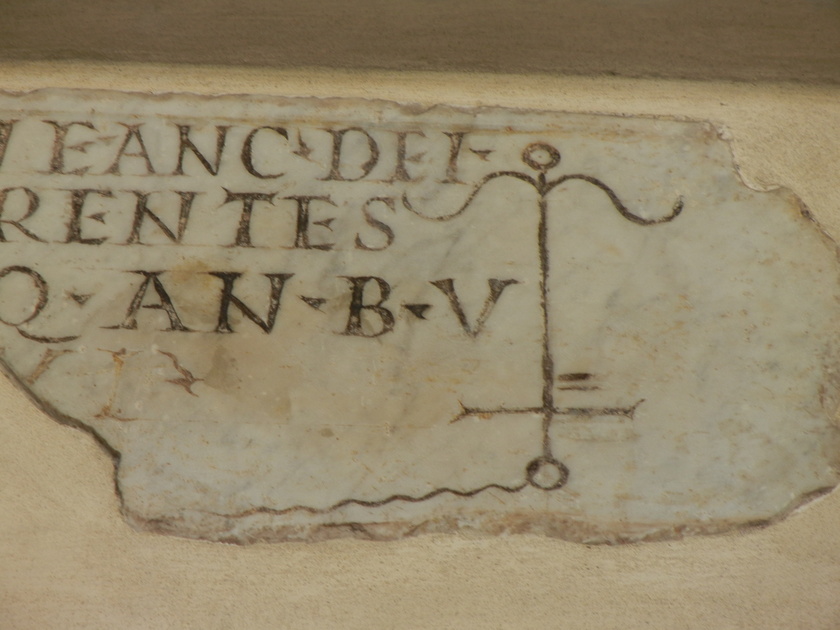

By the way, it is not true that Christians waited until after Constantine had discontinued crucifixion as a method of execution to use the cross as a symbol for the Church. It was there much earlier, though often disguised within other symbols, like ships, anchors, and monograms. Early scribes even wrote little crucifixes into texts to abbreviate words like "cross." Here's a photo I took of a funeral marker with an anchor (which by itself is a sign of faith). But notice that the anchor is upside down, so that it also forms a cross.

I mentioned in The Journey that I wrote a song based on Isaiah 2, which is one of my favorite OT passages:

In days to come, the mountain of the Lord’s house

shall be established as the highest mountain, and raised above the hills.

All nations shall stream toward it. Many peoples shall come and say:

“Come, let us go up to the Lord’s mountain, to the house of the God of Jacob, That he may instruct us in his ways, and we may walk in his paths.” For from Zion shall go forth instruction, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

He shall judge between the nations, and set terms for many peoples.

They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; One nation shall not raise the sword against another, nor shall they train for war again. House of Jacob, come, let us walk in the light of the Lord!

I hope you like the song!